Gilles Peress

At the Convergence of Art and History

Gilles Peress

Gilles Peress is a distinguished photographer and teacher with more than 34 awards, ranging from several Alfred Eisenstaedt recognitions to an ICP Infinity Cornell Capa award, as well as several grants and fellowships including those from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Guggenheim Foundation.

His work is in the collection of The Museum of Modern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the International Center of Photography, PS1, all in New York; the Art Institute of Chicago; the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; the Getty Museum in Los Angeles; the Minneapolis Institute of Arts; the Walker Art Center; the Victoria and Albert Museum; the Musée d’Art Moderne; Fotomuseum Winterthur, amongst others.

Peress has published seven books chronicling conflict, the Iran hostage crisis, the Bosnian atrocities, genocide in Rwanda, and post September 11 New York City, among them Haines (2004); A Village Destroyed (2002); The Graves: Srebrenica and Vukovar (1998); The Silence: Rwanda (1995); Farewell to Bosnia (1994); and Telex Iran (1984, 1997 reprint). Peress is currently preparing to publish a book on Northern Ireland: Whatever You Say, Say Nothing.

With a concern for the lives of the less fortunate, Gilles Peress turned to photography as a means of communication. “Words are often never strong, smart or subtle enough to convey the enormity of reality”, he stated. “I grew up in France at a time when turmoil in Algeria and Vietnam were shaking our view of the world.”

Peress studied political science and philosophy and that helped formalize his need to be involved in the world. During the course of his academic pursuits, a frustration evolved. It was the sense that at that time (late 1960’s) there was a growing gap between language and reality. Gilles picked up a camera.

Using a 35 mm camera, he set out to capture the tragic conditions suffered by French coal miners after a failed strike. He admits, “I had no training in photography. I knew that it was a means for me to stay sane.”

“I realized that I needed to look for assistance in becoming a better photographer. There were no schools, no grants. What was the path into photography? I went to Magnum Photos to ask, ‘How do I do it?’ I left a box of pictures with a secretary. I asked: “can some one talk to me?” She showed the box to Henri Cartier-Bresson, who said, ‘fantastic!’ I got a call back from Magnum Photos, to ask if I could work with them. That was six months from when I got into photography.”

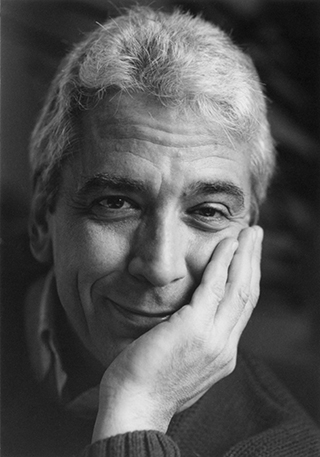

Gilles then began a life work in documenting the civil war in Northern Ireland. A study of the Turkish laborers in Germany, and the effects of migrant labor on Europe, became a second theme. In 1979 Peress spent five weeks documenting the US hostage crisis in Iran which became a book Telex Iran. The book depicts the people of Iran, as a study of their ways and customs, during the boiling point of the US embassy seizure. The next projects covered the siege of Beirut, the 1984 Democratic Convention in San Francisco, the Ku Klux Klan in Alabama, and Wall Street in 1987, amongst others. In the following years the genocides in Bosnia and in Rwanda were documented both as a visual narrative and as a reflection on justice.

Goma. Hutu refugees after operation turquoise. 1994

The evolution in projects required significant thought and insights – not just as an observer, but also as a professional photographer. Working quickly with the cameras and lenses implied a steep learning curve to make photography an unobtrusive tool.

“Whatever I do, I have to teach myself. That goes until today. I have to figure out how it works. We do everything here ourselves in the studio. We have a darkroom, a full digital process with a scanning area and a digital printing side. To a large degree I needed to reinterpret the digital technique, based on the analog experience. I worked hard at making the photography transparent. My film cameras were calibrated with processes so that I could work quickly. Everything needed to perform predictably, so that I did not have to think about the equipment.”

“What did I learn from the analog photographic process? I learned that for photography to be an expression, it needed to be fluid. It had to be transparent from the time that I saw the photo until it was translated to a print on the wall. It had to happen without my thinking about the technical side.”

“The biggest difficulty in digital - has been how to go from the file, whether digital acquisition or scan, to print with faithful reproduction in simpler ways. In the early days of digital imaging, the headaches were huge. We needed to learn ICC profiling, file handling, monitor calibration, and printing.”

“We started with the Radius Pressview in the CRT days. I spent a lot of money on screens over the years. Nothing was easy. The print process was especially difficult. We also started with the Cactus RIP and Encad printers.”

“Now the print side is much easier and more reliable. The EIZO displays allow us to see the detail we will get in the print more accurately. I am thrilled with the on-screen reproduction of tonality and detail in the EIZO monitors.”

“Our prints now match the images that we see on our displays. That is critical, as we are simultaneously working on producing pieces for fine art exhibits, prints for collectors, images for the books we are publishing, and work prints from ongoing projects which I am developing.”

Whether photographing aggression in Northern Ireland, Bosnia, Rwanda, Iraq or Afghanistan; the experiences and the imagery contain statements on life and death. Asked about personal safety, Gilles responds, “I am a very methodical person. I am also methodical here in how I approach production. The same is true in the field. Risk is really risk management. I go into areas with a calculated risk.”

“It is the same way in production. I do not want unpredictability in production. Once you calibrate and profile, you can run accurately and professionally. I set up boundaries and systems in the way I live life and in the way I produce images.”

In spite of looking death in its face, Mr. Peress does not comment on his own mortality. He shifts instead to the people and their circumstances around him.

“I have had intense experiential relationships over periods of time with people and subjects. I am producing a book which covers 20 years in Northern Ireland. I am working on another book which sums up my whole experience in the Balkans. There are cycles of involvement. Each of them has differences in visual strategies in tonality, narrative and emotional structure.”

“I will not transport what I learned in Northern Ireland into the Balkans. I will not take the Balkans experience into East Jerusalem. I approach each situation with the required equipment, small format digital, medium format digital, or film.” Peress continues to split his imaging between digital and film almost 50: 50. “I love the expanded contrast range which photographic negatives provide. Some locations such as Jerusalem demand control over extreme highlights and shadows.”

Gilles’ assistant, Marion added, “We have been using EIZO displays for seven or eight years. The latest CG246 is even more life like. With the AdobeRGB gamut, we are able to see reds, greens, cyans and blues more accurately than with any other monitor.”

Gilles Peress with his ColorEdge CG246.

“The self calibration gives added confidence that we are hitting perfect contrast and tonality. We see it in the images. Subtle detail on the monitor and in the print now match accurately.” This is extremely critical as Gilles is a master of detail and tonality. The content of his images are often rich with nuance. As a matter of counterpoint, the highlight detail and separation contribute toward the texture of the image. The EIZO CG246 reproduced each of the displayed images with delicate accuracy.

While rich with the craft of photography, the images are compelling with the subject matter of war and oppression. “Tens of thousands people died in a Rwandan refugee camp in Goma, Zaire while I was there working. While the work is at times difficult, I see myself in history. For me, photography and art are ways to begin to understand history for myself, by myself, it’s a process that cannot be encumbered by technology.”